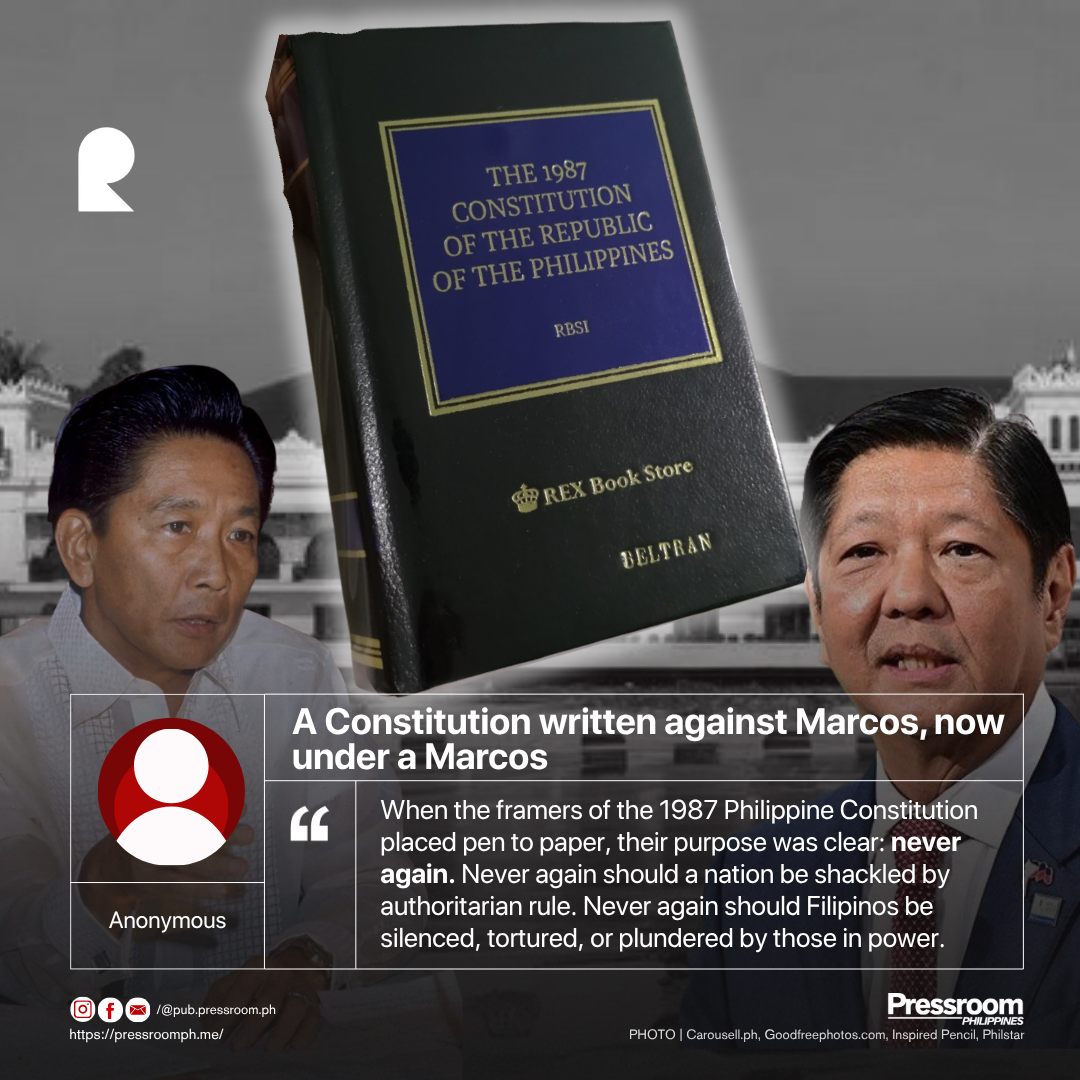

When the framers of the 1987 Philippine Constitution placed pen to paper, their purpose was clear: never again. Never again should a nation be shackled by authoritarian rule. Never again should Filipinos be silenced, tortured, or plundered by those in power. The entire document—the Bill of Rights, the term limits, the independent commissions—was born from the ashes of the Marcos dictatorship.

Yet here we are, decades later, under the rule of Ferdinand Marcos Jr.—the son of the very man the Constitution was written against. A bitter irony, a historical déjà vu, a paradox that reveals both the resilience and fragility of democracy.

But is this not the ultimate test of the 1987 Constitution? That despite the Marcoses’ return to Malacañang, they must govern within the very limits designed to restrain them. They cannot extend terms indefinitely. They cannot shut down dissent with martial law without oversight. They cannot, at least on paper, trample on human rights with impunity.

Still, one cannot ignore the political amnesia that allowed this comeback. What the Constitution sought to prevent, the people themselves permitted through the ballot. Democracy, after all, is only as strong as the memory of its citizens. And when collective memory fades, when history is distorted, the ghosts of the past sit once again in the halls of power.

The question now: will the 1987 Constitution be strong enough to withstand the very dynasty it was designed to block? Or will it crumble under the weight of revision, manipulation, and historical denialism?

We stand at a dangerous crossroads. To defend the Constitution is not merely to defend a piece of paper—it is to defend the promise of “never again.” And if we fail to uphold it, then perhaps the tragedy of our nation is not that Marcos has returned, but that we ourselves have forgotten why he was gone in the first place.